A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man Art

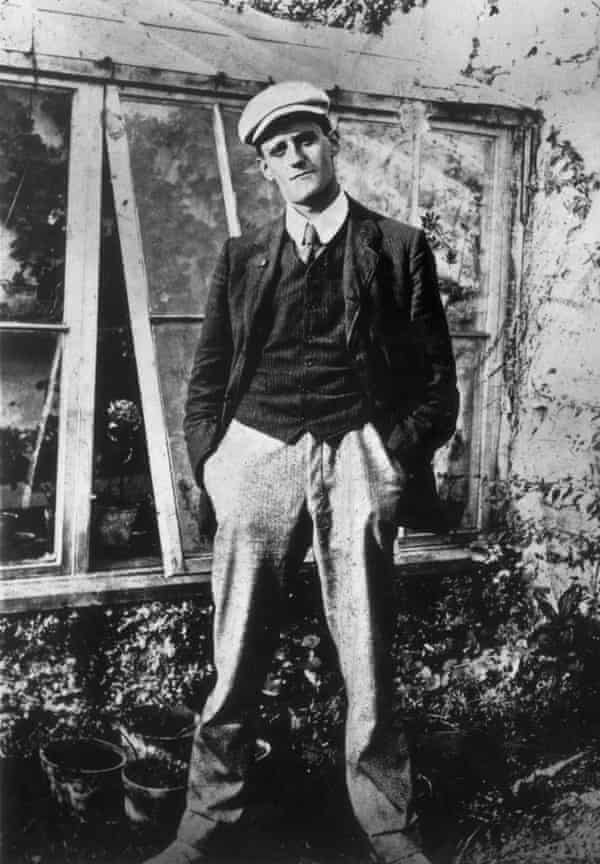

J ames Joyce's A Portrait of the Artist as a Swain begins with the conviction, ease and innocence of a story told to a child and ends with a tone that is hesitant, suspicious, fragmented and estranged. Between the 2 comes the teaching of 1 Stephen Dedalus, as the nets of race, religion and family endeavour to ensnare his tender soul and complex imagination.

Stephen is a born noticer and an circumspect listener. He is likewise someone who tin take himself and his experiences with immense seriousness and and so, a few pages later, put on an ironic disposition, as though his own very thoughts and the sufferings he endured were made to be fictionalised. (The before version of the book was chosen "Stephen Hero".) In A Portrait, at that place is a constant and nourishing disharmonize going on between the artist and the beau, the artist concerned with manner and texture and the refraction of experience, the young man with registering what he saw and remembered, how he grew.

For many Irish male writers who came subsequently Joyce, from Frank O'Connor to John McGahern to Seamus Heaney, the sifting of early on retentiveness, the detailed clarification of parents, domestic space, school, religious belief, came with the matching account of the young artist'southward effort to navigate these through solitude and reading, through cognition and linguistic communication.

In an essay written in 1982 to marking the centenary of Joyce's birth, the Irish poet John Montague, who died earlier this calendar month, a writer who had as well mined his ain childhood, wrote of the influence of A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Homo: "No ane could overestimate the effects of [the book] on afterward Irish writers … Or on the national psyche: many young Irishmen came to painful consciousness reading those corrosive pages. The Dublin of my student days was strewn with versions of Stephen Dedalus, including myself, though I wonder what the women thought of information technology!"

"Fiddling failed saints," Montague wrote, "we knew eternity too early." Almost every section of Joyce'south book belonged to common Irish gaelic Catholic experience. Aged 8 or nine, once a week, in Enniscorthy Cathedral, with the lights dimmed, nosotros heard the priest intone: "Expiry comes soon and judgment volition follow, so now, dearest children, examine your consciences and find out your sins." When I read the hellfire sermon in A Portrait, I had heard some of those very words, even though I was born forty years after the book came out.

The Christmas dinner scene, with the bitter argument about Parnell between Stephen's father and his aunt, could easily have come from many Irish tables in the 1970s and 80s equally families rowed over what was happening in Northern Ireland.

Since corporal penalty in schools continued until as recently as the early 80s, anyone who had the misfortune to be educated by priests or Christian Brothers (or indeed nuns) would have fully recognised the scene where Stephen is unfairly punished. Information technology happened to us all.

When I went to work as a language teacher in Barcelona in 1975, with many English people amongst my colleagues, I was constantly aware that how they spoke and how they saw linguistic communication was utterly different from how I did. When in that location was discussion over the pronunciation or meaning of certain words (or the use of "bring" and "take", which are different in Republic of ireland and England), I felt much equally Stephen did when he met the English Jesuit. "The linguistic communication in which nosotros are speaking is his before it is mine. How different are the words habitation, Christ, ale, master, on his lips and on mine! I cannot speak or write these words without unrest of spirit. His language, so familiar and and so foreign, volition ever be for me an acquired speech communication. I have non made or accepted its words. My vocalism holds them at bay. My soul frets in the shadow of his linguistic communication."

But, similar Joyce, I before long got over this feeling and saw that the best English was spoken in Lower Drumcondra. I soon took the view also that received pronunciation was, like all language, both a gift and a burden, and the distance betwixt united states a sort of joke. "It seems history is to blame," every bit Haines the Englishman says in Ulysses.

The afterwards sections of A Portrait, which movement between the National Library in Kildare Street and the halls of Academy College Dublin, could easily have taken identify in the early 70s when I was a student there. The fierce fence among young men near poetry and fine art, the sexuality in the air, fervid and repressed all at the time, and the demand to make urgent plans, as a mode of winning the argument, to leave Ireland altogether, belonged to the urban center I knew as much as to the metropolis of Joyce's book.

Joyce's genius was to brand this affair, to get the tawdry, common business he called in the book's last paragraph "the reality of experience" and to brand information technology both immensely foreign and worthy of the earth's close attention. He gear up out, as he wrote, "to forge in the smithy of my soul the uncreated conscience of my race" past finding a tone and a course to advise that the irksome, provincial city we lived in could be fabricated the centre of the known universe.

He used the thought of a port metropolis, a place that had once known glory but was now downward on its luck, as the perfect locus for a modern novel. The unevenness of his Dublin would exist matched by the mixture of dubiety and pride he would evoke in his prose. A Portrait has elements in common with Thomas Mann'south Buddenbrooks, another novel set in a provincial city, published in 1901. The dramatisation of the early life of a budding artist in Dublin and Lübeck would presently exist followed by the piece of work of Italo Svevo in Trieste, Fernando Pessoa in Lisbon and Jorge Luis Borges in Buenos Aires, every bit they attempted non only to remake themselves and their cities, merely besides to refashion fiction itself, to make it new, equally Joyce did, so that as soon as Ezra Pound saw the first chapter of A Portrait in Jan 1914, he set about organising the volume's serialisation. Joyce connected to piece of work on the volume into 1915, merely since he liked the thought of a book taking a decade to brand, he ended it with: 'Dublin, 1904.' And so below that the place to which he had fled: "Trieste, 1914." Ulysses, on which he would now embark, would take 3 years less to write.

Source: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2016/dec/29/colm-toibin-james-joyce-a-portrait-of-the-artist-as-a-young-man

0 Response to "A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man Art"

Post a Comment